Home Wireless Networks

Most people set up their home network using one of two different types of device;. They might have a wi-fi access point like the NetGear WG602, particularly if they already have some other devices to provide their Internet connection. Or they might have a wireless router, like the NetGear DG834G, which combines the wireless access point with a router (and perhaps also an ADSL or cable modem), all in the one box. Now, to the "passwords":

A home network wi-fi access point has two (2) different "passwords"; a wireless router has three (3). These are:

1) the administration password

2) the wireless network encryption key

3) the login name and password to authenticate to your ISP

Taking each of these in turn:

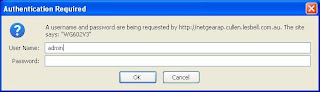

1) Admin password. This lets you log in to the access point or router through a browser interface and administer it (change settings, etc.) When you log in to the device, you will see something like the screenshot below. Your Kindle and other network devices do not need to know this password.

Fig 1. The login prompt for a NetGear WG602 wireless access point

2) Wireless encryption key. This is used to encrypt the wireless traffic so that bad guys can't sniff it and see what you're doing, or join your network and use your Internet connection to download pr0n, leaving you with explaining to do when the Feds come knocking. The key is really a long binary number, but because humans aren't very good at choosing - let alone remembering - long binary numbers, wireless devices also have an option that will turn a passphrase (not necessarily word) into the key. All devices that connect to the wireless network have to use the same key or passphrase, including any Kindles.

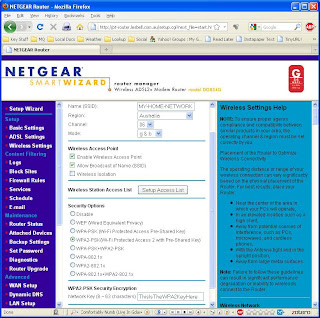

This passphrase is set when you configure the wireless side of your router, as shown here. Other things you should note are your network name or SSID, and the type of encryption in use - I recommend WPA2 with Pre-Shared Key (WPA2-PSK) as WEP and WPA are easily crackable.

Fig 2. Wireless settings on a NetGear DG834G wireless ADSL router.

For WPA2, the key is 256 bits long, and some routers will let you directly enter it as a string of 64 hexadecimal digits (that is, the digits 0-9 and a-f [upper or lower case]). However, you can enter a passphrase of up to 63 characters, and the router's logic will combine that with your network name (technically known as the SSID) in order to generate the 256-bit key. Because the SSID is also used in this process, it's a good idea to choose an unusual SSID (not the default, for sure) and then a passphrase of as few as 16 characters will keep you adequately secure.

Keeping the passphrase short is a good idea when you have to enter it into devices like the Kindle, where the keyboard isn't the greatest or there's no keyboard at all. Entering the 64-hex-digit key directly probably isn't a great idea, because not all devices can support that - it's best to stick with the passphrase technique.

But remember: it's still generating an encryption key, and it's best to keep calling it that to distinguish it from the other passwords involved.

[For the technically-minded, the way the router generates the key is using an algorithm called PBKDF2 (Password Based Key Derivation Function 2), which applies the keyed HMAC-SHA1 function 4096 times over, using the SSID as salt, which makes rainbow tables attacks infeasible].

If you didn't set up your encryption key (good grief, why not? It's your network!) then you might find the default value on a label attached to the bottom of the device. But it's good practice to come up with your own passphrase/key.

3) Routers also have a username and password which authenticates the router to your Internet service provider via your cable or ADSL connection. No other devices need to know this information.

So there you have it. Make sure all these bits of information are written down somewhere and stuck in the book where you record all your important computer information. And, notice, the Kindle only needs item 2), the WEP/WPA/WPA2 encryption key, which you will usually enter in the form of a passphrase (though I still insist on calling it a key. Because that's what it is).

To set up the Kindle, press "Home", "Menu" and then select "Settings". The Kindle may ask if it's OK to turn wireless on - click "OK". A list of visible wi-fi networks will appear, and you should see your own, with the SSID that you set up on your access point or router. Select it and you will be prompted to enter the WPA2 passphrase discussed above. Your Kindle should now connect.

Your network might not appear because it is set to not broadcast its SSID (a weak security measure). If that's the case, then use "enter other Wi-Fi network" to enter its SSID and password. Generally, the Kindle will detect the type of encryption being used, but you can also click on the "advanced" button and set that manually.

Public Networks

Many coffee shops, libraries and other public spaces now offer free wi-fi to customers. Generally, the Kindle will connect automatically - just use "Home", "Menu", Settings", "Wi-Fi Settings" and look for the network by name.

Sometimes such networks require you to indicate acceptance of their terms and conditions, and they do this by getting you to click on a button on a web page. Until you do this, the wi-fi connection will not work. In some cases, the Kindle detects this and will pop up a little message that asks you if you want to use the browser to connect to the network - you should do this and read the resulting page, then navigate to and click on the button.

Company networks, university wi-fi networks and others may also require you to have an account and log in, via user name, student ID and password. Again, the Kindle usually detects this and will offer to start the browser. It attempts to load the Amazon home page, but this will be redirected to the enterprise network authentication page, and you will need to navigate to the right fields and enter your credentials in order to log in. Once this has been done, the browser then usually proceeds to load the Amazon page; at this point, you can either continue web surfing or press "Home" and proceed to sync, download books or whatever you need to do.

The important point is that for some, semi-private, networks you cannot sync and cannot download books, periodicals, etc. until you have authenticated through the browser. So if the Kindle is not downloading properly, it's generally a good idea to see what the browser is showing.

Other Problems

Generally, attention to the above points - especially correct setup of a WPA2 key - will get your Kindle connected. However, occasionally it may fail to connect. Here's some general advice:

Disable MAC filtering. It does no good at all from a security perspective, since an attacker can observe which MAC (Media Access Control) addresses are in use on your network and set his device to use one of them, thereby bypassing that particular defense. Really, it does no good and just makes work for you, the network owner.

If you have an older N-type router or access point, make sure that you upgrade to the latest firmware for it. Many manufacturers announced and shipped "N" devices before the IEEE 802.11n standard was ratified, with the intention of fixing any incompatibilities later, with firmware upgrades. Also make sure that it supports both 20 and 40 MHz channel widths - 802.11b/g devices use 20 MHz only, so if the router is set to 40 MHz only, it will not be compatible. So make sure that you've upgraded the firmware. In some cases, I'd guess that a firmware upgrade alone won't do the trick, and the answer might be to disable "N' mode (configure the router to use only 802.11-g and/or 802.11b), or to buy a new router or access point. It might also be worth disabling "N" mode as a test.

Update (13/1/2012): It seems that the Kindle 4 and Kindle Touch use an Atheros AR6103 wi-fi chip. Looking at the "Product Bulletin" for that chip, it appears to implement only a small subset of the IEEE 802.11n standard. There are several new technologies that make 802.11n so much more effective: operation on both 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz bands simultaneously, use of multiple streams simultaneously over multiple MIMO (Multiple Input / Multiple Output) antennas, and the use of 40 MHz channel widths. However the AR6103 only utilises a single stream, and appears to utilise 64 QAM encoding over a single 20 MHz channel only. As a result, it achieves a maximum data rate of 72.2 Mbps only, which is not much improvement over 802.11g's 56 Mbps.

Worse still, it looks like this partial implementation of the 802.11n standard is what is "confusing" many routers and access points, so that the Kindles cannot associate with them. As described above, firmware upgrades, at least enabling b/g compatibility or even disabling "n" operation might be required, as might disabling 40 MHz-only channel widths.

As to what's in the Kindle Fire, I'm still in the dark. It seems to be a Texas Instruments WiLink 6.0 chip, but whether it's a WL1271 (b/g/n only) or the less likely WL1273 (a/b/g/n) is still unknown.

Hopefully, this will help folks get their Kindles connected.